May 25

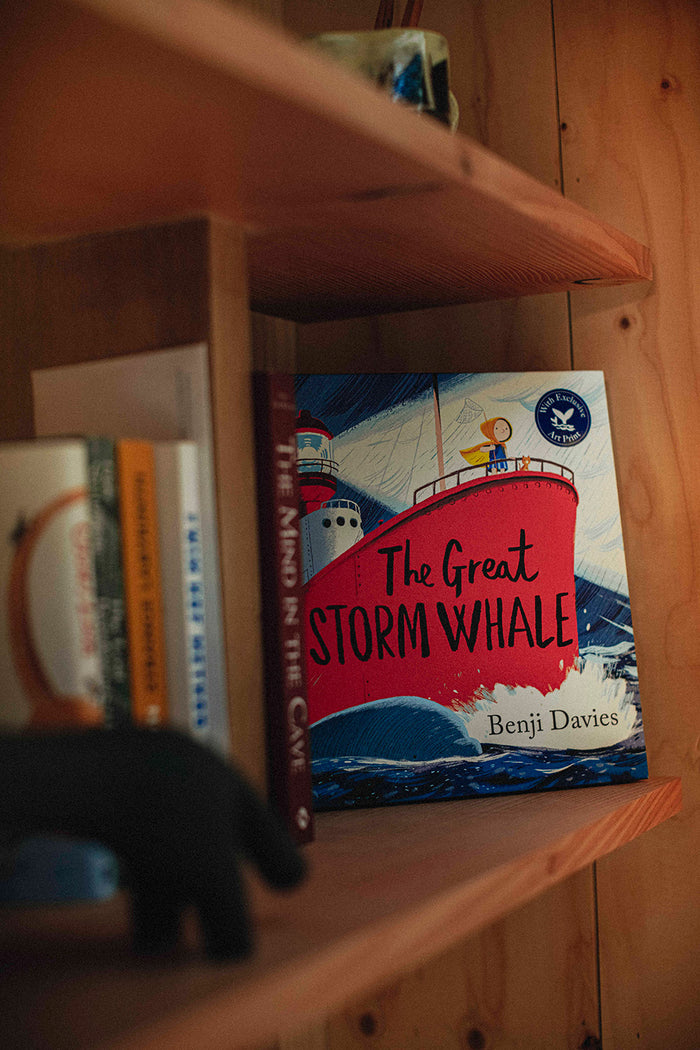

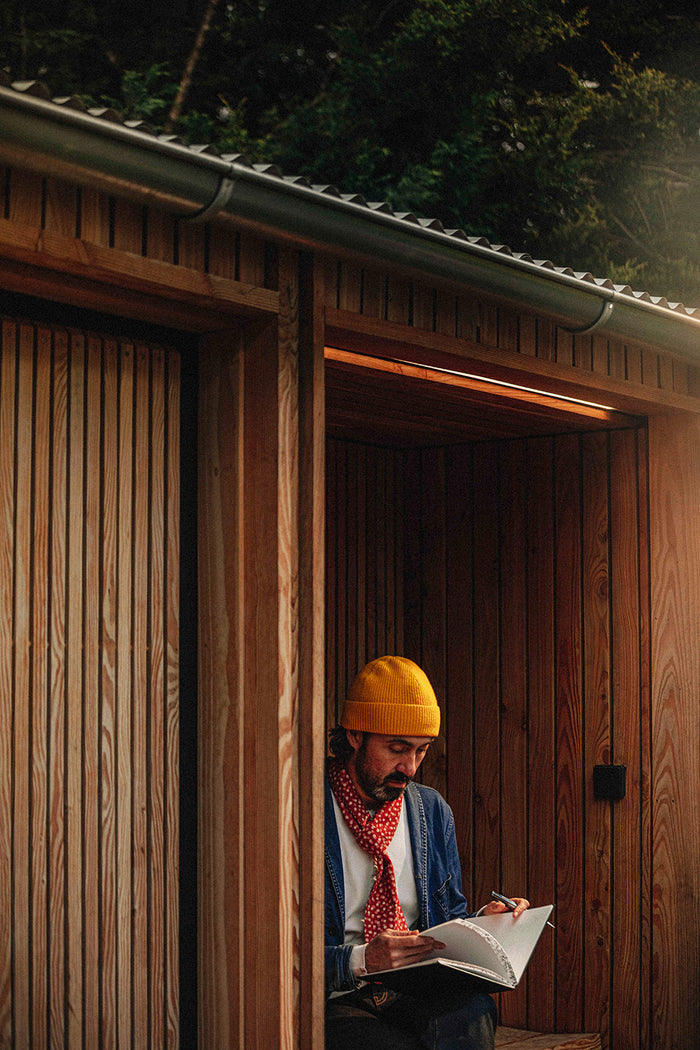

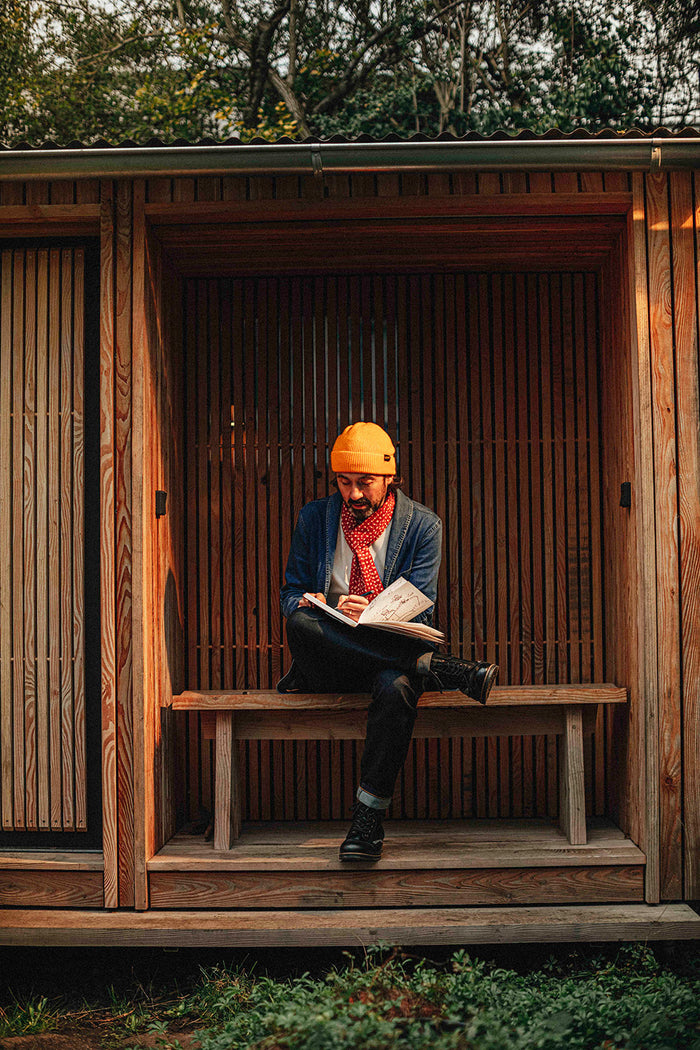

The Stories We Tell: An Interview with Award-Winning Author & Illustrator Benji Davies

As part of our ongoing Pioneers Series, we had the pleasure of sitting down with award-winning author, illustrator, and storyteller Benji Davies. Best known for his much-loved picture books The Storm Whale and Grandad's Island, Benji’s work is celebrated for its warmth, depth, and ability to explore life’s big themes through simple, heartfelt narratives.

In this conversation, we delve into Benji’s creative journey, from his beginnings in animation to becoming a two-time winner of the prestigious Oscar’s Book Prize. We explore how his stories take shape, and how personal moments often grow into universal stories.

As a creative working through a rapidly evolving digital world, Benji also shares his honest views on the rise of AI in the arts, the importance of human connection in storytelling, and the timeless value of things made by hand. A conversation about craft, intention, and the quiet courage of creating work that matters...

Can you tell us who you are and what you do?

My name’s Benji Davies, and I write and illustrate picture books.

You’ve been selected as one of our pioneers. What’s your definition of a pioneer?

I think being a pioneer, in what I do, is making your own unique path, writing and illustrating books, finding new ideas, and taking a unique perspective on children’s books.

Can you tell us a little more about the journey that led you to this point?

I started out studying animation, then did a bit of illustration for children’s books alongside whilst I was trying to find work. I became a director of commercials and music videos. Still, I was really looking to create more of my own work that was based around storytelling, which is why I studied animation in the first place. I wanted to tell my own stories.

I’d been to Whitstable in Kent for the day and saw these amazing beach huts. I did some sketches of them, and it took me back to a film I’d made as a student, about a little boy who finds a whale on the beach, takes it home, and puts it in the bath. I started developing that idea into what became The Storm Whale. I haven’t looked back since - that was 10 years ago now. I’ve now written eight picture books and also illustrated for other people.

That leads us nicely to The Storm Whale, which is now celebrated as a modern classic. Can you share your journey of creating that book, the process, and the impact it’s had on your life and career?

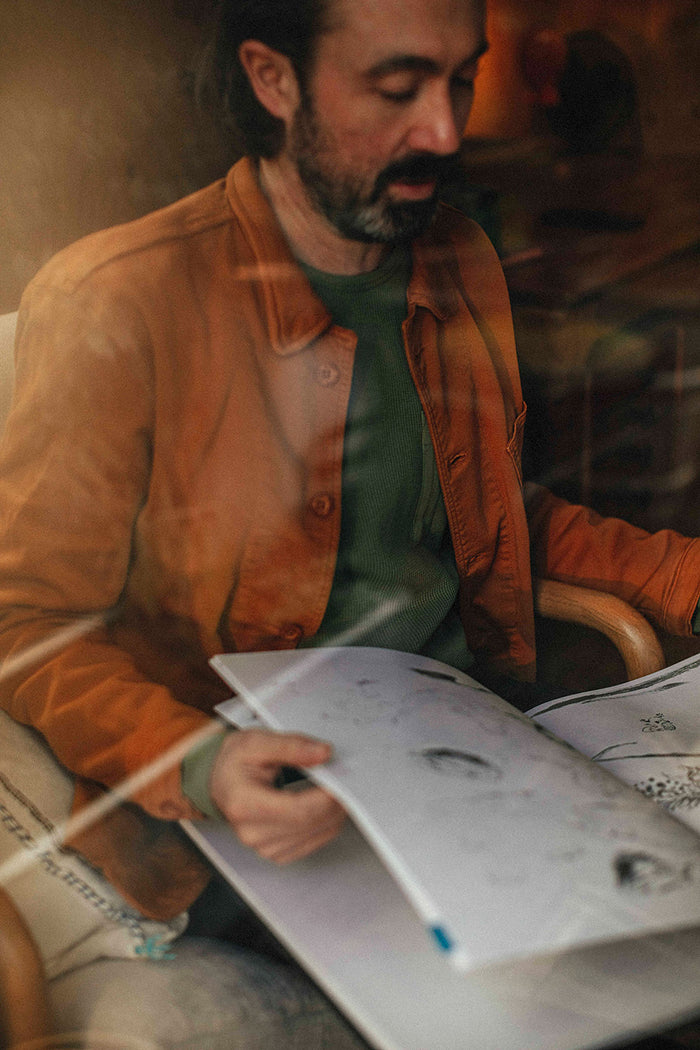

Often, when I’m writing, things start with a drawing. It might be something that’s sat in a sketchbook for a long time. I’ll see something in it that has a quality about it, which could become something else. It’ll sit there, maybe for years, and I’ll poke at it, try a few things out, and it’ll always be somewhere in my mind.

There are always seeds of ideas sitting in my head. Subconsciously, you’re working on them, collecting things that come together informally into a story. Then, one day, there might be a moment when a first line comes to me. It feels like I’m channelling the idea.

That happened with my book Tad. The opening line was, "Tad was a frog. Well, that’s not quite true. She was almost a frog." That sentence came from a drawing I’d done of a tadpole. It took me on a chain of words and thoughts that led to writing the whole story in one sitting, maybe five or six hundred words initially. Then it’s a process of editing.

I storyboard everything out, creating the world and characters. I lay out thumbnail drawings, the same scale as a book spread, and arrange them in InDesign to create a digital version, like a PDF dummy book. Then I continuously revise that, adding text, moving things around, and seeing what works. Sometimes, there's a prompt. For example, with The Storm Whale in Winter, I had no intention of making a sequel, but I thought, What would happen to Noi in Winter? That question led to imagining frozen seas, blizzards, him walking across the ice - and suddenly, a story’s there.

Throughout this, I collaborate with the art director and editor to refine the text and artwork. It’s a three-way collaboration. Together, we work on the dummy until we agree it’s ready to become the final book.

How much influence does the publisher have on the final book?

It’s very collaborative. I come up with the idea and the story, it’s very much my project, but I work in tandem with the publisher to produce the final piece. They guide it as much as you need and want them to, and as much as they need it to be marketable as a book. It’s about finding the balance between those things.

How do the themes in your books come about? Some authors can be quite heavy-handed with themes and messaging, especially in children’s books. How do you approach that?

I don’t really look at them as themes. I try to focus on character and setting, and what comes out of those scenarios. There might be something I want to tackle narratively, and that’s the challenge.

In Grandad’s Island, for example, the core idea was that I wanted to write something about grief and my own experiences. I wanted to express that people passing away is a natural process, but not labour that point. I wanted to tell it as part of a story about two characters. In that case, it’s Sid and his Grandad.

It’s a kind of fantasy journey. The point is there, but I never want to hit people over the head with it. The way it evolved, especially for very young children, they don’t actually know that’s what it’s about. They just see it as an adventure story.Then, when they get a bit older, maybe six years old, they begin to see the layers. People have told me their children have had those moments of realisation.

Suddenly they realise, "Oh - is that what it’s about?", but I’m never putting myself in a position of being an educator. I don’t want to deliver some heavy moral.

I suppose I’m coming from a place of thinking it’s good to open up dialogue around these things. But I’m definitely not focusing on that when I’m doing the final work. I hope it just comes through in the soul of the work - transmitted through the illustrations and words.

You’ve won the prestigious Oscar’s Book Prize twice, what does that mean to you personally? And was that always something you wanted from becoming an author, or was it a byproduct?

When I started out writing picture books, the idea of having a story I’d written and illustrated published was my only goal. Nothing beyond that. So to be here, ten years later, still doing it, with The Storm Whale now published in over 40 languages and winning awards - it’s incredible.

Awards are fantastic for opening up your work to new audiences. It’s brilliant recognition. But beyond that, it’s about getting those ideas and stories out to more people. That’s what matters to me.

The Storm Whale has been adapted for the stage - how did that feel? And how involved were you in bringing that to life?

There’s this incredible moment when you see the production for the first time. I wasn’t too involved in the run-up. I had a few conversations with Matt Aston, the director, about the books and how he might adapt them. But then he just got on with it.

Then, you go to a preview and you see all these little details, props and sets, based on things you once drew. I remember sitting there, looking at a trunk on stage, and thinking I remember the day I drew that in my studio, imagining what it might look like. And now, there it is.

And it extends to the characters too, like Noi’s dad in The Storm Whale. They made him this chunky, bright turquoise wool jumper, just like I’d drawn. It’s surreal. They’ve created this whole thing behind the scenes, and suddenly you’re sitting there watching a three-dimensional version of something that started in your head.

How does living in East London influence all this?

I’ve lived in London for about 15 years. First in Hackney, then I moved to Walthamstow around 10 years ago. I’ve thought about leaving a few times, but there’s just so much energy here.

I’m especially drawn to the history of London. If I’ve got meetings in central London, I’ll cycle or walk between places because there’s so much to see. You turn a corner and find something you’ve never noticed before. It’s constantly shifting.

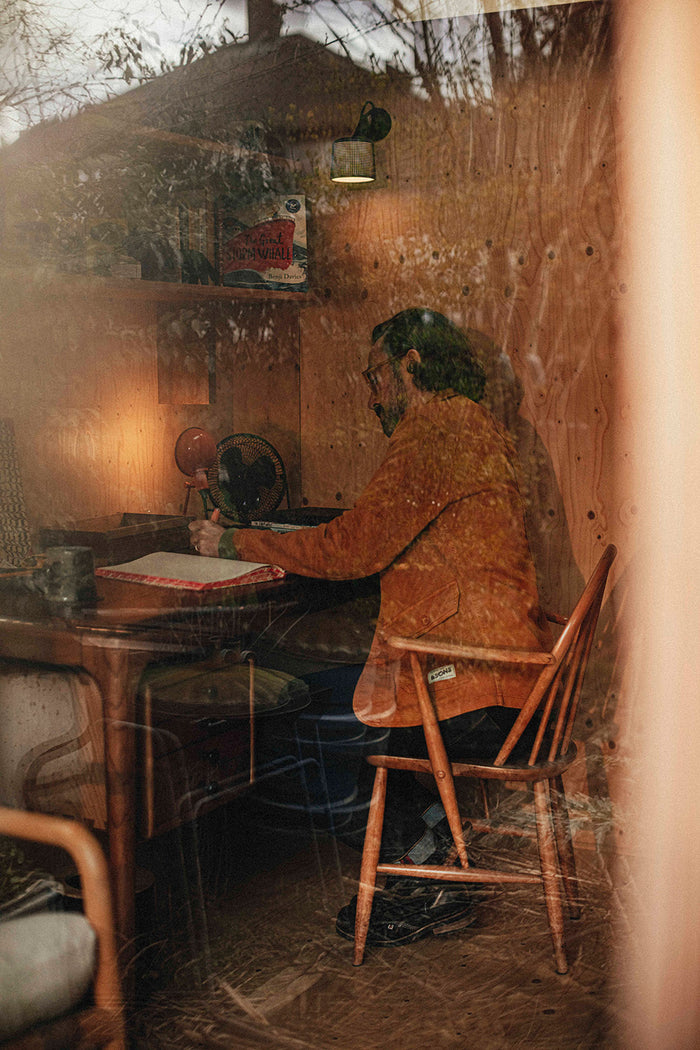

Now we’re on the edge of Walthamstow, and you can hear birds in the trees. I’ve got this shared studio now, and I love the peacefulness of it.

The best part is, that central London is only 20 minutes away by train, and just round the corner is Epping Forest. It’s the perfect balance for us - peace and quiet, but with the city on your doorstep.

You mentioned pivoting in your career when the world was going through its own shifts. So for anyone considering a career change or starting a creative journey, what advice would you give?

I think being true to yourself is so important, especially in creative work.

That’s what spurred me to start writing and illustrating picture books - a need to tell stories from my own perspective. I’d worked in illustration, and in commercials, but I was looking for something with more personal satisfaction.

Whenever I’ve done any teaching or talks, I always say: make it personal. Draw the things you love, and write about what matters to you. It doesn’t have to be autobiographical, but those lived experiences - the things you absorb day to day, seep into your work. And eventually, they bubble up through the art.

People connect with those human elements. I think it’s even more important now. Personally, I’m trying to step away from digital a bit. I’ve worked digitally for so long, using computers and software, but I’m finding so much value in reconnecting with paint, paper, and the tactile nature of creating things.

There’s so much conversation about AI at the moment - are you optimistic, cautious, or somewhere in between about where it’s going?

We’re surrounded by so many distractions, social media and tech, and while AI is a brilliant tool, it’s also a threat, not just to industries like publishing or illustration, but to us as people.

We’re animals, essentially. The soul in a piece of work - the exchange between people, is so important. AI might mimic what humans can make, and it’ll get better and better, but we need to ask ourselves: why do we need that? Why not have actual things made by humans? Because humans can already make that. The soul of it, the lived experience, the hands that made it - you can’t replicate that.

It’s not to say don’t use AI, it’s incredible for research, for heavy lifting tasks. But we need to ask why we’re using it, and what our intentions are. Not just be led by it because it exists.

I remember using Quark before we all adopted InDesign. Even then, people were wary. But it’s about how you use these tools, and what for.

Besides your own work, who are the artists and authors that inspire or influence you?

I’ve always been inspired by a lot of mid-century artists, especially those used by Disney to create their concept work back in the ’50s and ’60s. Mary Blair would be one of those. And Gustav Tenggren, he worked a bit earlier, did a lot on Pinocchio.

I love illustration that combines brilliant draftsmanship with great use of colour and composition. A lot of those people Disney hired were incredible at that.

Beyond that, Eric Ravilious has always been a big influence. He was killed during World War II, but before that, his work in modernist landscape painting using watercolours was incredible. Beautiful light, colour, texture - and in a really modern way.

And then as a child, I loved The Tiger Who Came to Tea. I was very lucky to go and have tea and cake with Judith Kerr a few years ago, which was amazing.

What’s next on the horizon? Any exciting projects you’re able to share?

I’m currently working on something for older children. I’ve got about 40,000 words down on a big project, which, considering picture books are only about 500 to 1,000 words, is quite a change!

It might be a couple of years before it sees the light of day, but that’s the big thing I’m working on right now. Lots of words, lots of writing.

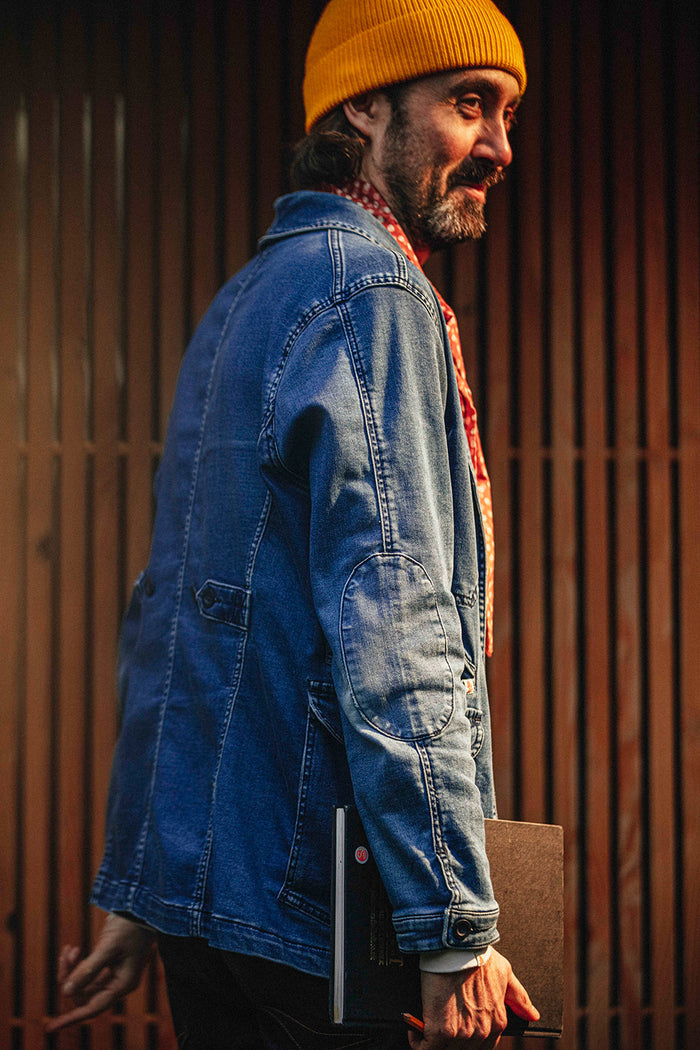

We’ve spotted you wearing a few &SONS pieces in some photos. What first drew you to the brand, and do you have a favourite piece?

Yes, my favourite &SONS piece is the Crafter Jacket. It’s just such a nice day jacket. I can wear it to a meeting, or throw it on at the weekend. It’s really versatile and just a nice, comfortable thing to wear.

And finally, will The Killer Cat make a comeback?

Hope so! Maybe in the new book. Maybe not quite murdering a pigeon this time… but we’ll see.

There are a lot more characters in a longer book. That’s one of the things I’m learning. With picture books, you’ve got one narrative, a beginning, a character, and an end. Once you’ve got those, you know you’ve got a story.

But in a longer book, you’ve got the overarching idea, then smaller little arcs and characters and threads that weave together. It’s more forgiving in some ways because a picture book has to be really tightly written, every line, every image matters. Nothing throwaway.

In a longer story, you can let some things be incidental, but they still need to feed into the bigger story so that, in the end, it all delivers something satisfying.

To discover Benji’s beautifully illustrated books or follow his journey, visit benjidavies.com or find him on Instagram @benjidavies