October 25

Pioneer Stories: Redefining Furniture with Christian Dunbar

What does it mean to be a pioneer?

To me a pioneer is somebody who's going somewhere where all the answers aren’t already figured out yet. And for me as an artist, I never do the same thing twice.

It’s always about discovering new materials or new processes or new artistic ways to handle things. It’s a little bit of my good and bad because I get stuck figuring something out rather than repeating what I already know. But it stays fun that way.

Can you share your journey as a furniture artist ?

In 2008 I had to start over when the market crashed. I went back to school in my 30s, got a couple of furniture design degrees, and I got into sculpture.

I was already middle aged, so I kind of knew how the world worked a little bit and I just went for it. I like pure form. I don’t want to do production pieces. I want them to be as artistically avant-garde as they possibly can be.

All the beauty for me comes from the glorification of the pure materials and showing wood, or leather, or concrete in a way that really shows off their inherent beauty. It’s all about the material and figuring out ways to express those materials that really exhibit their finest qualities.

What inspires your choice of materials for each project?

Once upon a time I was all polished. I wanted everything to be perfect and polished and beautiful. And I had a sculpture teacher say,“The shiny doesn’t look shiny if you don’t have some rough mixed in with it.”

Something went off and I realised you have to have both sides of it - for one to look perfect, the other has to look less perfect to exemplify that. At that point it became clear to me that wood was that organically perfectly imperfect material.

The things that go with that are those perfected industrial materials that adjoin it and become the pedestal that the organic is held up onto. For me, I am driven almost entirely by the beauty of organic materials and exemplifying those. I’ve found that the best way to do that is to take an industrial material; steel, metal, concrete., express that in a perfected way, and then let it become the pedestal for the organic material to be held up high.

Red Hook, Brooklyn is known for its artistic community. How has the local environment and culture influenced your creative process?

I live in Manhattan. I take the West Side Highway down every morning. And when you come to Red Hook, you’re surrounded by a hundred of some of the most renowned artists in America. You can’t help but be inspired by that.

There’s always somebody doing some kooky maker process, and you never feel like you’re doing anything other than what you should be doing. You’ve got glass guys, concrete guys, sculptural wood guys, carpenters - everybody’s out here on the waterfront.

If you’re not inspired when you come out here, then you’re dead.

Customisation is a key aspect of your creations. Can you share an example of a particularly challenging project?

The most challenging project I’ve ever done is probably one I’m working on right now. It’s a desk made out of solid sapele that will be cut and carved one three-inch layer at a time, stacked, and then carved again. It’s cantilevered.

I didn’t realise when I first designed this how heavy it would be, but it’s going to turn out to be about two thousand pounds. That joins together the elements of wood, computer design, and engineering.

Then there’s the logistics of transporting and moving a 2,000-pound piece of wood without breaking it, or without it breaking me. It has to be perfectly engineered, perfectly built, and perfectly transported down to Savannah, Georgia. It’s a tough one for me.

Handcrafting each piece implies a deep connection to your work. How does the hands-on nature of your craft contribute to your artistic expression?

Every one of my pieces is different. There’s no two that I’ve ever done where someone would say,“I want what you did for Miss Jones over there.” Everyone is designed in and of itself and then built in and of itself, based entirely on the details of the material itself.

I work around the material and not the other way around. Hands-on work hopefully leads to the best expression of those organic details that I try to glorify.

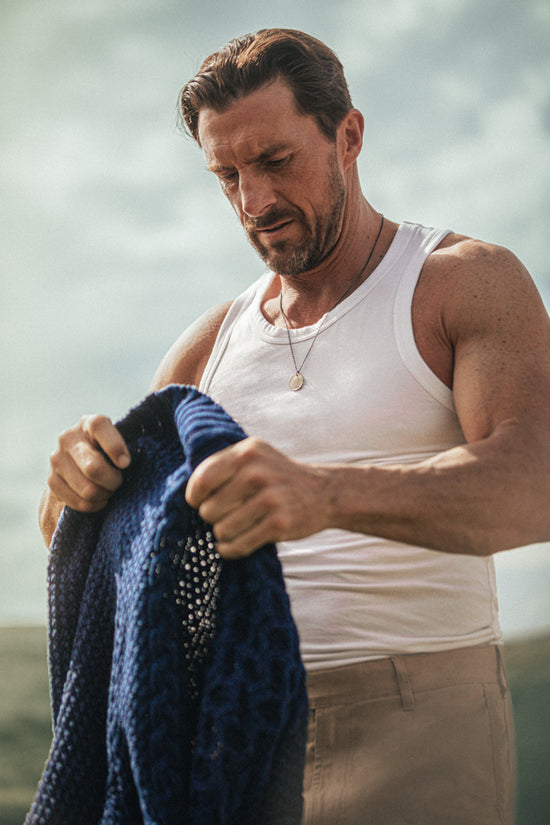

In such a physically demanding workshop, functionality is crucial. How does your clothing impact your ability to transition between design, creation, and hands-on work?

I’m in a busy collective shop with dust flying everywhere and heavy machinery going off every time you turn around. What you wear is a huge part of the consideration every day. It’s gotta be durable, and hopefully it won’t get destroyed by all the dirt. My favourite thing is wax clothing because it’s durable and it sheds off the dirt. I also love in the summertime something casual like what I have on today.

Red Hook has a rich history and diverse community. How do you draw inspiration from its culture and history?

Red Hook is this fanciful little nook of Brooklyn on the waterfront that used to be run by the Dutch. It was built 450 years ago in the 1600s. Now you have these huge old spaces that are filled with artists and collectors.

You can’t help but be inspired and reminded of what happened in these spaces four or five hundred years ago. They’re huge, and you can get just about any process done that you need to. That’s rare in New York. Here in Red Hook you have the artist community and the space to do these crazy things. I can’t think of anywhere else I’d rather be for doing what I do.

As a creative individual, how do you see the role of art and design in shaping the identity of Red Hook?

Red Hook was built 400 years ago by the Dutch. It was a big industry hub, and the old giant warehouses still exist today. Those have been turned into artists’ collaborative spaces, and they’re all just giant collectives like the one I’m in.

Every month you see huge custom pieces coming and going because there’s space out here unlike anywhere else in New York. The artists are all here. If I can just be part of that community, contributing to the influx and flow of some of the coolest custom pieces in the world, then I’m doing great.

Christian's dedication to glorifying pure materials, pushing boundaries of form, and staying true to hands-on craftsmanship makes him a true pioneer in both furniture and sculpture. Rooted in Red Hook’s vibrant history and community, his work not only celebrates the beauty of organic and industrial materials but also contributes to the ongoing story of creativity in Brooklyn. Follow along with his journey as he continues to create monumental pieces that balance innovation, tradition, and artistry.