August 24

&SONS Pioneer Stories: Joe Pantoliano

Joe Pantoliano, known for his performances in classics like The Goonies and The Matrix, has certainly left a mark on Hollywood. But beyond his cinematic achievements and impactful storytelling, Joey's involvement with &SONS has added another exciting chapter to his story.

As a devoted fan and customer of &SONS, Joey saw the potential in the original Crew Pants and suggested producing it in a new colour, sparking an enthusiastic collaboration. Phil and the team seized the opportunity to deepen their connection with Joe, travelling to meet him in person to truly understand his journey. This visit was not only about celebrating the new Joey Crew Pant but also about exploring the person behind the iconic roles and his broader impact on both film and charitable causes.

Join us as we delve into Joey’s rich career, his personal insights, and the collaborative spirit that brought Joey's Crew Pant to life…

The Goonies hold a special place in the hearts of many. Looking back, what memories stand out the most from your time working on this iconic film?

People ask me about my favourite experiences among all the jobs I've done, and I always say The Goonies. There's so much to remember. When COVID hit, we all got together on an email chat and reconnected.

What I remember most is all the pirate ship scenes. The largest stage in the world is Stage 16 on the Warner Brothers lot. They use it for water work and create little cities because the stage is so enormous. The water was where the crew set up cameras and lighting, always at three feet, but everyone was always in the water, so they had to keep it at about 83 degrees. Below the gangplank, they had built a hole about 16 feet, so kids could jump off into the water and not get hurt. One day, because of the heat and the temperature of the water, a cloud formed at the top of the rafters, and it started raining inside. They had to open the big stage doors on either side and bring down enormous fans to blow the clouds out. That stayed with me.

We worked six-day weeks because they needed to finish the film by a certain date for its summer release and I used to bring my three-year-old son to set. It will be the 40th anniversary soon.

Your career spans a diverse range of roles, from The Sopranos to The Matrix. Are there specific characters or projects that, while they may not have received the most attention, personally resonated with you?

There are many. A lot of films I did had mild successes that became cult classics. When you consider my body of work, I’ve been known to say that 95% of it is complete shit. The remaining 5% includes some classic movies that have stood the test of time. Some films have been discovered later, like Bound, the Wachowskis' first film. It had mild success; I don’t even know if it made its money back. It became a cult favourite within the LGBTQ community. It recently won an award for Best Drama Film Noir, which is pleasing to know.

There are smaller films I've done that I really enjoyed. I made a film in Italy called From the Vine, shot in a small town in southern Italy called Acharenza. I really enjoyed working on it, and it had great success because it was released during COVID. It’s a fun family comedy that was embraced by communities looking for a movie experience free from the traumatic content that has become popular. It was great. I love going to southern Italy, and Rome is my favourite city.

And are there certain rituals or approaches you consistently bring to your work?

Breaking down a script, building a character, and understanding who I’m playing—my wants, my likes—always guide me. I focus on the logical, continuous behaviour of the character according to the given circumstances. I ask myself who I am, where I am, and what I want. With film acting, TV acting, and acting in front of a camera, everything is done in pieces. Between action and cut, my intention is to understand what I want and what the conflict is. I try to keep myself open to happy accidents. The best moments in my work are not created by me; they come through me. I try to be available for the creative forces to come in.

Even as a filmmaker, when directing or producing, you come to understand that the movie has its own direction and determination of what it wants to be. If you remain open to these revelations, it helps. My trick is not to know the lines too rigidly but to leave room for spontaneity. Many filmmakers use the script as an outline and allow improvisation. I’m more interested in the behaviour of what I’m doing rather than just what I’m saying. Being sensitive to what’s happening and what’s coming at you is crucial.

In your extensive career, are there one or two stand-out moments or scenes that you're particularly proud of? And if so, what makes them memorable for you?

That's an interesting question. I’m embarrassed to admit that I don’t really remember specific scenes. In my old age, when I’m flipping through channels and see myself on TV, I might think, “That kid looks like me,” or realize it’s me in the scene, and sometimes I don’t even remember being there or shooting it. What I remember is the experience—the fun, the crazy things that happened on the job, the dinners, and the breakfasts.

A lot of my memories from The Goonies, for example, are from being in Astoria, Oregon. There was a Travelodge motel on the river next to a salmon packing plant. In the mornings, before we went to the shoot location, we would have breakfast at the hotel, which was catered for everyone staying there. It was great seeing the kids, their guardians, and the crew.

Back then, they were still shooting on film and had dailies. Some filmmakers were very rigid and didn’t want actors to attend, but Richard Donner had an open-door policy. The kids and crew would attend dailies, usually after the day’s work, around 6:15 PM, eating pizza and soda. It was a fun, collaborative environment with Donner and Spielberg working together. I learned a lot on that job.

One big lesson was when we shot a scene where my character slipped and landed awkwardly on a pole. Spielberg wanted to reshoot it with a specific idea—having me do a 360-degree backflip off a pole and land in a similar way. Donner was on board, and Spielberg arranged for a stunt double, Spiro Rosatos, who was a gymnast. After a week of practice, the stunt was performed in one take. This guy was so good that he never went back to school. Spiro became a prominent stunt coordinator, working on major films like Fast & Furious and Bad Boys. He's now doing that stuff because Spielberg had an idea of having my character do a 360 backflip. A career was born.

You're known for your involvement in various charitable activities especially for mental health. Can you share more about why these causes are close to your heart and any experiences that led you to champion them?

When I was diagnosed with clinical depression in 2008, I realized it had been with me my whole life. As a teenager, I thought that becoming a successful actor would make this feeling go away. However, as my success grew, the feeling persisted. I developed a lot of bad behaviour trying to fill the void within me. Eventually, with my family’s support, I recognised that I needed help and was ready to receive it

When the doctor told me I had a disease, it felt like I had won the lottery—it wasn’t my fault. I had always thought it was a personal defect. Getting the help I needed allowed me to return to work, as I had been unable to work for a period. For movie and TV work, insurance companies required evaluations to ensure you wouldn’t have a breakdown. When asked about my medication, I mentioned taking Lipitor for heart disease and an antidepressant for depression. A few days later, my lawyer informed me that the insurance company would not cover me due to the antidepressant. They suggested that if I signed a waiver, I would be responsible for any production delays caused by a breakdown. However, if I had a heart attack, they would cover it. I was so angry by this discrimination against mental health.

Talking to friends in the industry, many advised keeping the conditions private. This was frustrating because I felt I shouldn't have to lie. I decided to go public and, with a friend's help, started a nonprofit to raise awareness and support for mental health. This was over ten years ago, a time when high-profile individuals often labelled their conditions as alcoholism, which was less stigmatising than other issues. I realised that many people with substance abuse problems were actually dealing with underlying conditions like bipolar disorder.

I discovered that ADHD, which I learned about when my children were diagnosed, was a part of my own struggles. Understanding that mental illness is not permanent but consists of manageable moments and moods has been enlightening. Simple activities like taking a walk can increase serotonin and dopamine, helping to stabilize my mood. I understand the paralyzing nature of severe depression, where even a magical cure within reach seems unattainable.

I'm quite happy and proud of the part I may have had in getting people talking about it. You know, celebrities are talking about it entertainers are talking about it. You know you can get a laptop, you can go on your iPhone and have a session with your psychiatrist, it’s easy now. So that's pretty cool.

Actors often talk about finding a piece of themselves in the characters they portray. Have you ever played a role where you felt a special, deep connection or shared a similarity with the character?

Oh, yeah. There are always pieces of myself in the roles I play. In telling a story, this is a collaborative medium. This connection drives my desire to relate to characters on screen, whether on an iPhone or in a movie theatre. Filmmakers are telling their stories, and every movie I do is a piece of me. I convey the author's intention and the logical behaviour of a character, often addressing people from my past.

One reason I enjoy playing antagonists is that, as an adolescent who was overweight and bullied, I felt like a coward. Through these roles, I can confront those bullies and give them what they deserve, even if it's through a different character. If I’m emotionally begging for someone to get help, it might be directed at people I love who never received the help they needed. The audience doesn’t know what’s going on inside my head, so connecting with myself and moments of my own past are the things that I like to do when the material itself doesn’t speak to me and there’s some kind of mental blockage.

Which character resonated with you the most?

First of all, there's a great fallacy about how actors pick their parts. I'm an actor, I'm not a movie star. I'm a journeyman actor who gets picked. And depending on how much money there is in the bank and how much rent I owe, will determine what I say yes to. That's why I've got such an illustrious career of sh*t.

In the past, you were often paid more for less desirable roles. The characters that resonate with me are those that challenge me. I liked playing Teddy in Memento and Cypher in The Matrix. I felt Cypher was the most human character in the story because of his doubt and confusion. He took the wrong pill and the girl that he loves is in love with somebody else. He just finds a way out. Most of the time, people who are fans of that movie always say, "You were the traitor, you betrayed your friends.” I always have an argument with them about who wouldn't take that deal? Who is so miserable and unhappy that he could betray his friends and not ever have a memory that he did so? I think that's why it pisses people off so much. Because we all think we're the hero. Not many of us take the time to think about under what circumstances I would be willing to betray my father, my mother, or my brother. Under certain circumstances, as a human species, we're all capable of monstrous behaviour.

How does storytelling through writing compare to acting?

Storytelling through writing and acting are quite different. Acting is easier for me, especially the kind I do. In terms of creative arts, I find acting to be the easiest. It involves contributing your part to a piece without having to sit in front of a blank page.

When writing my books, I drew inspiration from stories I told at dinner parties about my family. I was encouraged to write a screenplay based on these stories, which led to a book deal. My collaborator, Maureen O'Brien, suggested structuring each chapter around an address I lived in, which made storytelling easier. I would record my stories and then transcribe and edit them.

Writing a book was a lot of work and not always enjoyable. Hitting a wall during writing is costly, unlike in acting where you can continue trying different approaches. The freedom between "action" and "cut" allows for private, exploratory work. For example, in Memento, which was shot out of order, I had to constantly check if I was portraying the truth. The challenge of conveying a character’s unreliable memory was part of the fun. Filmmaking has evolved significantly from when directors would watch through enormous Mitchell cameras to today’s video playback systems, which allow for precise framing but I've noticed that most directors are much more interested in the framing than the acting itself.

Throughout your life and career, how have you seen yourself grow as an individual, both personally and professionally?

My growth has been a continuous process. When I was very unhappy and emotionally broken, it was due to my reliance on various behaviours and substances to ease my soul. I describe these in my book as my “Seven Deadly Symptoms," which were symptomatic of the adolescent trauma that shaped who I am and drove me to become a performer.

Seeking and receiving help, along with the process of ageing, I’ll be 73 in September, has contributed to my personal growth. Recently, a friend and I were discussing the troubling idea of death, especially as we grow older and face the loss of mutual friends. My friend's sister lost her son, and the idea of death becomes increasingly daunting.

Interestingly, I've learned more about human behaviour from my dogs than from my therapist. Their ability to live in the moment contrasts sharply with our human awareness of mortality. We understand from a young age that we will eventually cease to exist, unlike other species. Humans create religions to assure themselves of a better afterlife because we find this life so challenging. Yet, religious friends often pray to overcome illnesses like cancer, which confuses me if they believe in a better existence after death.

Losing loved ones is often more about our own pain and loss than about the departed person. I sometimes find myself mourning the loss of my dogs more deeply than that of my parents, which might stem from the unconditional love dogs provide. They simply want to eat, sleep, and be present, a quality I am learning to embrace. I am becoming more comfortable in my own skin and in my own company, whereas in my younger years, I was afraid of missing out on something and struggled to be content in solitude.

Sometimes lesser-known films hold immense personal value. Are there any hidden gems in your filmography that you wish more people knew about or that hold a special place in your life?

Regarding hidden gems in my filmography, I don't have any particular films that I feel need more recognition. There are some films I wish had never been released and others that, if they didn't get recognition, they deserve not to because they were real clunkers, real stinkers. So I really have no opinion. I just wanna get the next job and the next job and the next job and do the best I can in between action and cut.

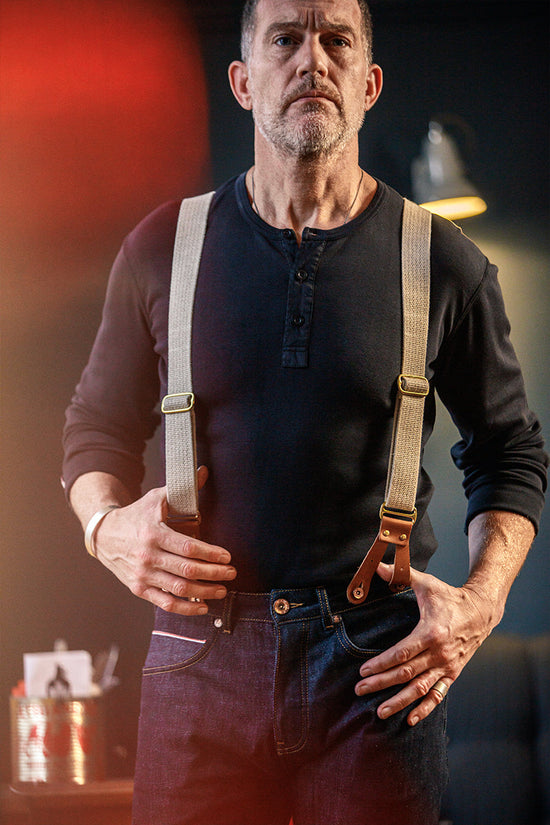

How do you see clothing as a form of expression, and how do they play a role in shaping your onscreen and offscreen identity?

Clothing plays a significant role in shaping my identity and building my character. I always start from the toes up when deciding who a character is, focusing on how they dress and carry themselves. For instance, in the play Rock and Roll Man this summer, I portrayed two distinct characters and aimed to make them as different as possible. Working with the costume designer, I treated the suit I wore in the first act as a seat cushion in my dressing room. It was wrinkled, with one pant leg shorter than the other, and I removed the elastic from my socks so they would fall to my ankles. In contrast, my other character was very polished. I had them find silk, see-through stockings, which were popular in the 50s, with seams every inch or so.

Growing up, my father was a very stylish dresser, and I wanted to emulate him. When I was around 12 years old, my family took me to the old Madison Square Garden on 50th and 8th Avenue to see the Ringling Brothers Circus. I was fascinated by the cowboy shirts, belts, hats, and boots that seemed emblematic of the circus, the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show and the rodeos that would come into New York City. I was drawn to this style and the practicality of Western wear, such as scarves that served a purpose, like protecting against dust or hiding one’s face during a robbery.

My attraction to your clothing line is rooted in its style and functionality. I didn’t know that snap buttons had a practical use, like preventing a shirt from tearing if it got caught on something. I appreciate the purpose behind these design elements. I also love the formality of being dressed from the waist up and the cowboy belts. When I first moved to California in 1976, I visited a famous Western store in Van Nuys called Nooties, which supplied clothing for figures like Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. I bought my first cowboy belt there and began collecting them ever since.

How did you get involved in a Western?

I appeared in an HBO Western called El Diablo with Lou Gossett Jr. and Tony Edwards. I played Truman Feathers, a Western author inspired by Truman Capote. I talked the director into giving me a mule so I could have my record player and all my cooking pans and I overdressed, I changed three times a day. As a result, I almost killed Lou Gosset Jr. because I had to schlep this mule behind me and there was like a week of training on horseback riding and mule lugging.

I was told by the Wrangler not to tie off the mule onto my saddle because if the mule runs off, he'll take you right off the saddle with him. So you just hold the rope and if the mule acts up, just let go of the rope. We had a sequence, where we were going through a cave, but this was in LA and the cave wasn’t a tunnel, it ended in a rock wall, but it was big enough to turn around and walk the horses out. Lou and I were doing our scene and as we were entering the cave, for some reason, the mule freaked out, Lou was in front of me and the mule took off and Lou's horse took off and all I could hear was an echo of Lou Gosset Jr. screaming, “oh shit, oh God, oh Christ” And I thought the mule was killing him, but luckily he got out okay.

With your wealth of experience, what advice would you give to young actors or creatives who are just starting on their journey in the industry?

I have mixed feelings about the future of entertainment. The process of storytelling has remained relatively unchanged since the days of Cecil B. DeMille, with people performing in front of a camera. However, now technology like AI and iPhones has transformed the industry. When I trained as an actor, it was for the theatre, but we were inadvertently learning film acting. Back then, auditions involved performing in person with a scene partner. Now, you can simply record a scene on your iPhone and send it in. The landscape has shifted dramatically.

In the past, becoming an actor was more of a challenge; few had the confidence and determination to pursue it. Being a performer often feels like a compulsion, a need to be seen and heard. If you have that drive, my advice is that it’s easier now to practice and create your own opportunities. You can collaborate with friends, write your own material, and make films with your iPhone. The more you can do, the better your chances of success.

A major question when I was starting out was how to sustain a career. It's not just about having one good year but maintaining success over the long term. It requires a plan and the ability to be fortunate. Success often hinges on being lucky enough to get a job, perform well, and have the project succeed, allowing you to continue working. My own journey began when I was 19. I attended acting school but didn’t earn a living for the first seven years. During that time, I made about $1,000 and worked as a waiter. This experience was valuable, as it taught me about interacting with people and understanding their needs, which helped me with my acting. The idea is to immerse yourself fully in the craft, whether it's through acting classes or working in related fields.

Betty Davis once gave the same piece of advice to aspiring actors: "Always take Fountain Avenue," which was a shortcut to the studio avoiding the traffic on Sunset Boulevard. Randolph Scott was a famous Western actor. This is the quote I wanted to tell you earlier, people would say, "Aren't you an actor?" And it’s his quote that I've stolen now. And I say, "I'm no actor, and I got over 100 movies to prove it."

Your openness about mental health and overcoming addiction has inspired many. How has navigating your own personal challenges influenced your approach to roles and storytelling in your career?

Recovering from addiction and dealing with personal challenges has deeply influenced my approach to acting. When you stop numbing yourself to avoid uncomfortable feelings, those feelings resurface. They’re not as frightening as one might think. Feeling emotions is essential to my work. During therapy, I was concerned that taking antidepressants might affect my ability to feel the emotions needed for my job. However, I discovered that experiencing these feelings and channelling them into my work was a release for me. Initially, I thought I was making myself crazy by dredging up old trauma and incorporating it into my characters. A psychiatrist later told me that this process of sublating unresolved feelings into my craft might have actually saved my life. Acting provided a positive outlet for my emotions and challenges.

So when you reflect on your career, what kind of legacy do you hope to bring behind both in the film industry and beyond?

I don’t feel I have anything to prove as an actor. I’m indifferent to how people perceive my work, whether they think it's good or bad. The reason why I wanted to be an actor was because I wanted to be inside my mother's 12-inch black and white TV. I wanted the ability to leave evidence that I had existed.

Watching old black-and-white movies as a child, I was fascinated by the idea that, although the people in the films were long gone, their presence was preserved. This desire to leave a mark is why I enjoy watching classic films. I love watching black-and-white movies for several reasons. One is I love being able to see what the world was like then and how it dressed. I'm still waiting for the fedora to come back. But the other thing is I feel less jealous or competitive because if I see movies that are just been made and I see something that I could have done and that I wasn't in it, it pisses me off.