May 25

Roll The Bones: “Eyes Up”

By Chris Nelson

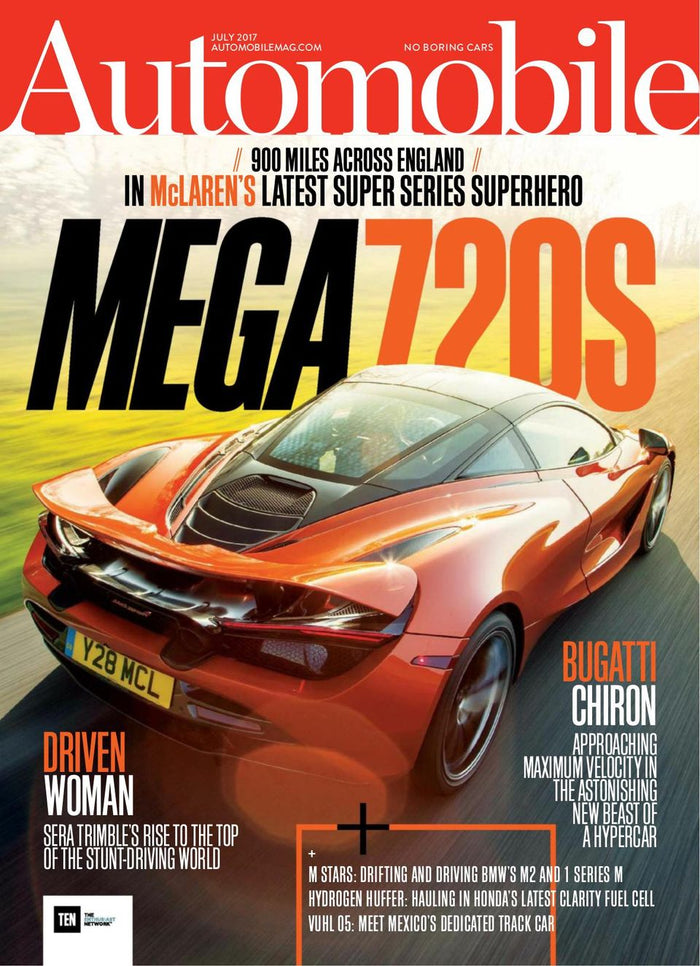

A decade has passed since I wrote my final cover story for the out-of-print Automobile Magazine, in which I detailed the near-death experience of losing control of a brand-new McLaren 720S at 140 miles per hour on Goodwood Motor Circuit in Chichester, England.

It was one of the most powerful experiences of my life, and I often reminisce on how terrifyingly wonderful it felt to push that British-made, twin-turbocharged, 710-horsepower supercar to and just beyond its incredible limits of grip and speed, and live to tell the tale.

A singularly special feeling stirs in me as I drive at the limit. I first felt it on the day I got my driver’s license, which was immediately revoked for recklessly ignoring the speed limit. It felt dangerous, wild, and free, but I had no idea how transformative that feeling could be until my time at Automobile Magazine, where I learned to drive faster than I ever imagined possible.

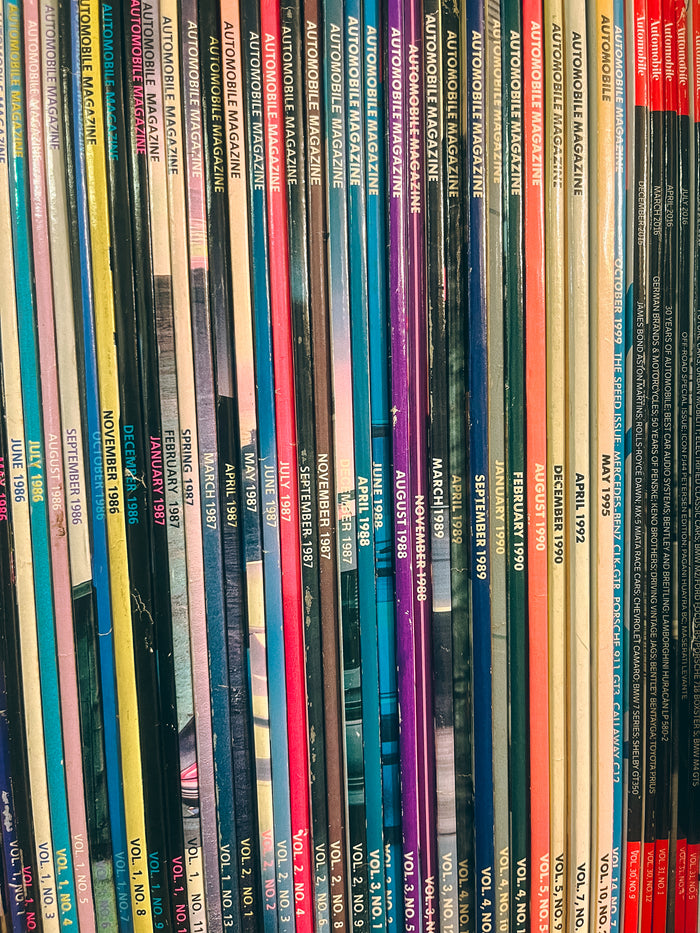

First released in 1985, Automobile was founded by the late David E. Davis, a visionary man with a moustache almost as fantastically large as his ego. Davis assembled an incredible team of misfit hot-shoes who wrote damn fine stories, took damn fine photographs, and crafted an artful monthly rag that celebrated “no boring cars.”

My first job out of college was as road test editor at Automobile Magazine, which meant I was responsible for managing and maintaining the constantly changing fleet of never-before-driven test cars that came to and from our office in the “Pretzel Bell” building at 120 East Liberty Street in downtown Ann Arbor, Michigan.

At the very bottom of the magazine’s masthead sat my name, and as happy as that made me, I so desperately wanted to climb the ranks and prove my worth to the senior editors, who were immensely talented writers, creatively ambitious experts of magazine craft, cuttingly honest critics, and incredibly fast and exacting drivers.

At the time I was damn sure that I was a damn good driver, because throughout my youth I had enjoyed many nights of illegal high-speed racing on the streets of Chicago in an Acura Integra with blue neon lights and two, 12-inch subwoofers. It turns out that street racing doesn’t teach you much in the way of technique, and I was simply a big-headed, square-jawed boy at the sweet and stupid age of 22 years old who somehow managed to fill his pockets with the keys to all the coolest, fastest, and most dangerous toys in the world.

My ego desperately needed to be humbled, and it happened only a few weeks after starting at Automobile when I attended my first track day at Gingerman Raceway, a modest, 2.1-mile, 11-turn grassroots racetrack on the outskirts of the adorable lakeside town of South Haven, Michigan.

I drove a third-generation Mazda Miata roadster, which any automotive journalist would agree is an ideal car for a first track day, and I felt especially cocky because my dad owned a first-generation Miata that I often hooned and slid around in on the streets of Chicago. In my mind, I saw myself behind the wheel of the Miata, rolling out of the pits and onto the road course, doing heel-toe gearshifts, powersliding through corners, and maybe even setting a new lap record, earning the desired admiration of my fellow editors.

But it was an abysmally shameful day, filled with messy cornering, botched gearshifts, missed apexes, and blown-by braking points; it was like I had never driven a car. Frustrated and embarrassed, I wanted to quit my dream job, move back home, buy a beat-to-shit hatchback, and give up on track driving, because clearly I didn’t have the talent to keep up with my peers and properly evaluate high-performance cars.

After a night of woe and whiskey, I licked my wounds, shook off the self-loathing, and set my sights on becoming one of the most capable hot-shoes at Automobile. The next day I went back to Gingerman and instead of trying to showboat, I slowed down, left the car in third gear, and learned how to drive around the track without braking or shifting, which proved much more difficult than expected.

Week after week after week, I returned to Gingerman, each time in a different car, and slowly but surely I learned the basics of track driving. Some of my editors took notice and offered guidance by sitting in the passenger seat, telling me to turn into corners so smoothly that if there was a bowl of water on the dashboard, it wouldn’t spill, or engage the brakes with so deftly that if there was an egg beneath the pedal, it wouldn’t crack. I listened, and my laps got quicker and more consistent.

The best advice they gave me was also the simplest: “Keep your eyes up.” When you’re driving an automobile around a road course, it does not matter much where you are on the track, but it matters a lot where you want to be. If your focus is too shallow, you cannot assess the turns ahead, which means you will not properly set up for entry, and you will likely skid past the apex, struggle through the corner, and maybe even lose total control of your car, which can be fatal. If you keep your eyes up, though, you can stay in control while pushing your car to its limits; the further you look ahead, the faster you’ll get there.

Once I started looking up, there was no looking back. After months of obsessively learning how to drive on track, my editors rewarded my much-improved abilities by assigning magazine stories that took me to racetracks all over the world.

In a snowstorm at Barber Motorsports Park in Birmingham, Alabama, I challenged the grip of four, huge slick tires on a 505-horsepower, track-tuned Chevrolet Camaro Z/28. On a winding road course carved into the granite hills of Palmer, Massachusetts, I turned countless laps in a 500-horsepower Acura NSX. On the iconic Formula One track in Japan, Suzuka Circuit, I hustled around in a heavily boosted prototype car built by Subaru Tecnica International (STI). Through the iconic “Corkscrew” at Laguna Seca in Monterey County, California, I went flat out in a 887-horsepower Porsche 918 Spyder hybrid hypercar.

The final racetrack I went to was the Goodwood Motor Circuit, where I was the first automotive journalist to drive the completely new McLaren 720S supercar. On my first run down the back straight of the historic 2.4-mile road course that in June 1970 claimed the life of the automaker’s founder, Bruce McLaren, the 720S exceeded 170 mph, and as I buried the carbon-ceramic brakes and watched the active rear wing raise to act as an air brake, I fell madly and deeply in love with the car.

Hours of high-speed driving passed by in blur and without incident, until the end of the day, when I went flat out down the track’s front straight, got up to 140 mph, and kept the accelerator pinned to the floor as I turned into a fast righthand bend with a slight dip. When the 720S passed over the dip, its rear end immediately stepped out, and I counter-steered as quickly as possible to avoid the concrete retaining wall that the supercar was skidding toward. Miraculously I managed to keep control, flick the 720S back straight, and hobble back to the pits, where a track marshal told me he didn't see any difference in driving style or line from previous laps, and asked how I was doing. “I want to still be out there,” I said. “I would take that corner the exact same way again and again and again.”

The following day, I visited the McLaren headquarters in Woking, unsure of what I’d done to cause such a harrowing experience, expecting to be berated by angry engineers who had scoured through vehicle telemetry data and found my every mistake. Instead they welcomed me with open arms, told me that I was on pace with the factory test driver, and things went wrong because I overheated the tires. They said that I should either start driving track-built cars on racing slicks to familiarize myself with the feeling of heat build-up, or I should slow down.

I did neither and instead came to a full stop. Every week for years, I drove the world’s most impressive cars as fast as I could around the world’s most beautiful road courses, and it should’ve been the happiest time of my life, but I was miserable.

My dad died the year prior. He was an avid reader of Automobile Magazine from the beginning and even had one of his letters to the editor published in the October 1986 issue. After my dad was gone, I realized how much I loved him being my biggest fan and rooting me on, and it became impossible to have fun at my job knowing that I could no longer share my stories with the person I loved most.

Automobile Magazine was dying, too. I achieved my goal of ascending the masthead and becoming a senior editor, but it was bittersweet because all of the best editors had been fired or had quit. After egotistical corporate vampires stepped in, reorganized leadership structure, and sucked the soul out of a once-great publication, Automobile Magazine became an unsurprised mess that I no longer recognized or respected, so I quit.

While writing and editing led me down strange, exciting new roads, none of them took me back to the track, and every day for the last ten years I have tried desperately to feel that singularly special sensation that I once knew so well. It is still there, asleep in the dark inside of me, and every now and then it pokes its head out of the shadows.

I feel it when I race rented go-karts around a small, local track outside of Denver, Colorado, or when I drive my first-generation Miata up into the tight mountain passes in the Rockies. I can even feel it during especially heated races against my fiancee when we play Mario Kart on our Nintendo Switch.

Even so, none of it gives me the full effect of that sensation, and I must accept that I likely won’t feel it again. However I am grateful for so intimately getting to know that feeling, which is one that very few humans will ever experience, and I am thankful for the Automobile Magazine editors who took the time to teach me how to keep my eyes up.